Despite constant indigenous technological improvements, changes in materials and tastes, and the influence of foreign ideas, there are certain fundamental features in Chinese art that allow it to be described and recognized, regardless of the place, age, or purpose of its production. These essential qualities include love of nature, belief in the moral and educational capacity of art, admiration for simplicity, appreciation of accomplished brushwork, interest in the vision of the subject from different angles and fidelity to widely used patterns and designs. Chinese art was to greatly influence that of its East Asian neighbours, and worldwide appreciation of its achievements, especially in ceramics, painting and jade work, continues to this day.

The Purpose of Chinese Art

One significant distinction between China and many other ancient cultures is that a significant number of Chinese artists were amateur gentlemen (and a few ladies) who were also scholars rather than professionals. Students of Confucius and his practical teachings, they were frequently poets and men of letters. They and their audience used art to represent and communicate the philosophical outlook on life they cherished. Because of this, most of the art they created is simple and plain, occasionally even seeming austere to Western eyes. For the most of China’s history, art was not just a means of showing off one’s technical ability, but also a means of expressing the excellent character of the creator. Many people who created and appreciated art sought Confucian ideals like property or li.

Of course, there were other artists who worked professionally, employed by the imperial court or affluent clients. Of course, thousands of artisans also created works of art from priceless materials for the wealthy few, but they weren’t regarded as artists in the contemporary meaning of the word. Calligraphy and painting were the actual fine arts in China. If there is any elitism in the contemporary art world, the Chinese may have been the first to give in to debates about what constitutes art and what does not.

As people’s understanding of art has increased in China, more and more people are starting to collect it. With helpful categorization of the many accomplishments of historical artists, texts have been created to help readers navigate their way through the history of Chinese art. In a way, art has been standardized, with rules that must be followed. As part of their education, artists were forced to examine the works of the past masters and replicate them. One of the most famous and enduring sources of advice for judging art is the six-point checklist by Xie He, art critic and historian of the sixth century AD, published at the originated in his now lost work, Ancient Record of Painters’ Classifications. When considering the merits of a painting, the viewer should assess the following (point 1 being the most important and essential):

- Spiritual resonance, which signifies vitality.

- The bone method, which consists of using the brush.

- Correspondence to the object, which means to represent the forms.

- Suitability to type, which relates to the location of the color.

- Division and planning, i.e. placement and layout.

- Transmission by copy, i.e. the copying of models.

Therefore, the idea that art should, in some way or another, benefit the viewer is largely to blame for these very strict standards for the production and appreciation of art. Only in more recent times has the notion—or, better yet, the acceptance—become widespread that art can and should convey the emotions of the artists themselves. This is not to imply, however, that there haven’t been eccentrics who disregarded tradition and produced masterpieces in their own unique style throughout history.

Calligraphy

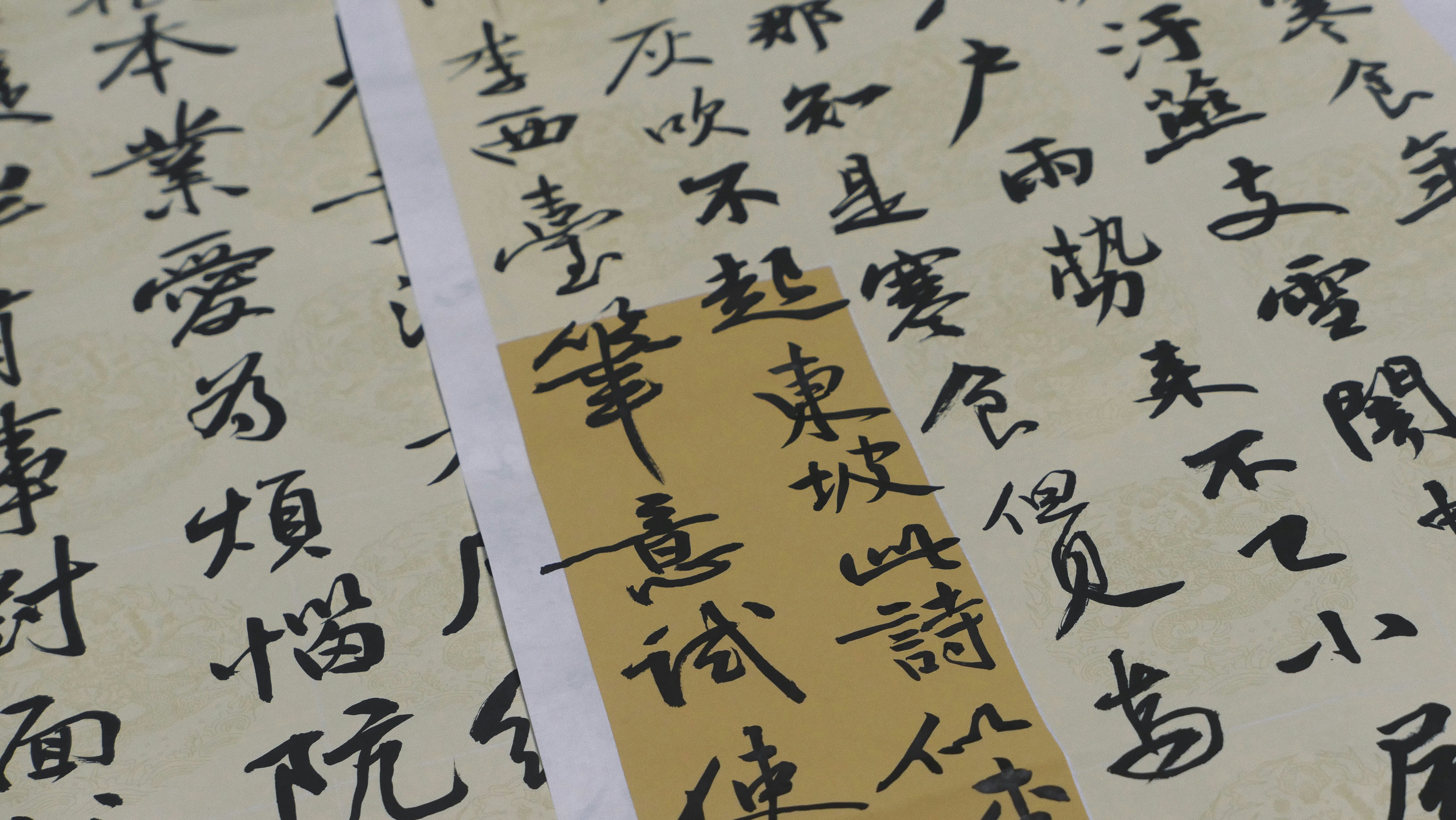

[caption id="attachment_343387" align="alignnone" width="1120"] Chinese art calligraphy[/caption]

Chinese art calligraphy[/caption]

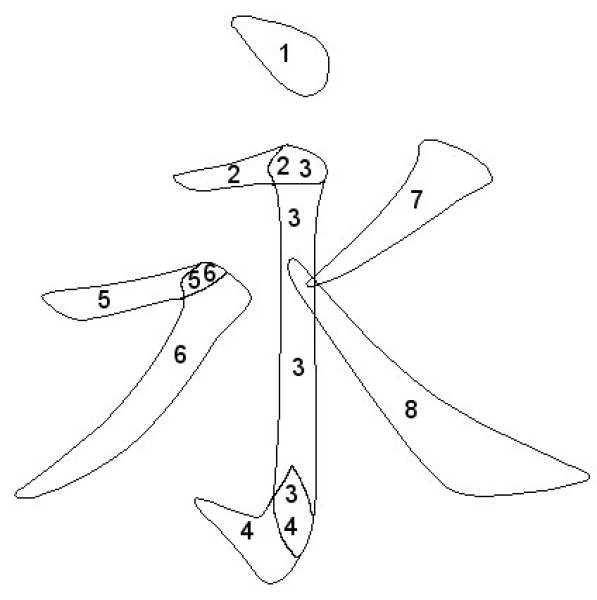

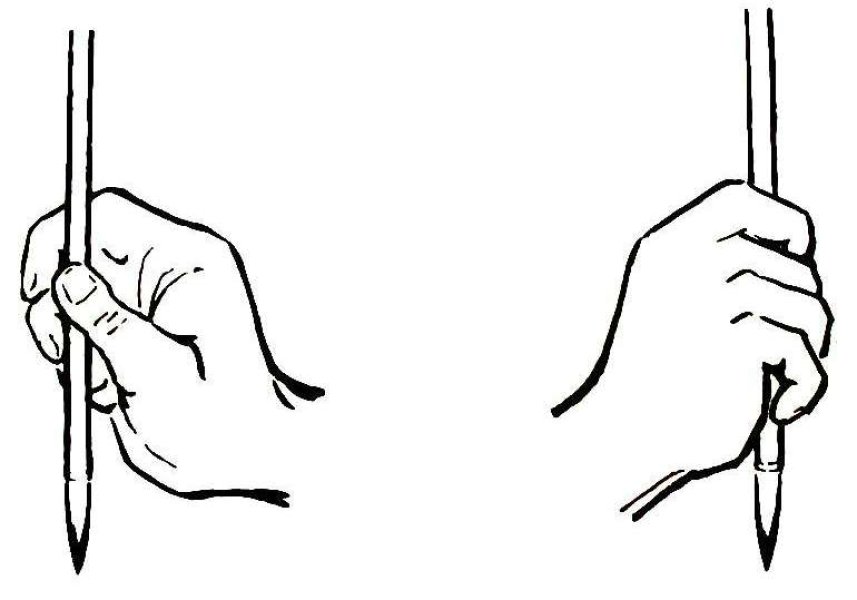

Chinese calligraphy, 书法 (shūfǎ), literally “beautiful writing”, is the art of writing Chinese characters, traditionally with brush and ink. It is one of the most distinctive features of Chinese culture. This type of expression was generally held in high esteem throughout East Asia and notably influenced writing in Japan. The art of calligraphy – and for the ancient Chinese it was certainly an art – was intended to demonstrate superior mastery and skill with brush and ink. Calligraphy established itself as a major art form in China during the Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) and for two millennia all educated men were supposed to master it Chinese calligraphy is a unique phenomenon in the history of mankind, both in its breadth and in its artistic achievements and the peculiarity of its aesthetics which inspired the art of Chinese painting. Long before the introduction of pen and pencil in China, millions of people practiced the art of writing with brush and ink.

Why do the Chinese place such importance on the art of calligraphy?

Calligraphy has long been revered as the pinnacle of visual art, not only a type of decorative art. It was regarded as a form of self-expression on par with poetry and esteemed even higher than painting and sculpture. Even while calligraphy has long been regarded as a fine art, its importance in Chinese culture is unparalleled. To create beautiful calligraphic lines, a calligrapher coordinates the brush, paper (or silk), and ink while managing type size, contrast between light and dark, and speed of application. It is not only a method of communication, but also a means of expressing emotions.

In China, it is commonly accepted that calligraphy expresses the author’s personality. It is said that an individual’s character, disposition and mood, as well as his good or bad fortune, can be accurately determined from his handwriting. It is one of the 4 noble arts of China, with a connective dimension where Chinese language, history, philosophy and aesthetics merge, and the way one writes is as important as what one writes.

An artist can achieve a surprisingly wide and rich array of artistic effects that eloquently convey the artist’s personality and the mood of the moment of inspiration. The suppleness of the brush allows the subtle changes of pressure, direction and speed to be transmitted, transmitted from the calligrapher’s shoulder, to his arm, to his wrist and finally to the fingertips. This explains the unique ability of calligraphic brushstrokes to capture with great liveliness and immediacy the kinetic energy that passed through the body of the calligrapher during the creative process.

The essence of calligraphy stems from the raw magic of simplicity

Western culture prioritizes things that are measurable or quantifiable and can be rationally or scientifically explained. Asia has a different outlook on life that is firmly anchored in a love of magic, nature, and everything that is irrationally unfathomable. This connection to nature serves as the foundation for all calligraphic theories.

Many great artists have been moved by the straightforward sounds of a stream, the gentle movements of a dancer, or the sound of rocks tumbling. This is the reason why the art of calligraphy is so elusive and difficult to categorize. Long before it emerged on paper, at the center of the universe, calligraphy was made. Many masters have been inspired by the simple sounds of a stream, falling rocks or the graceful movements of a dancer. This is why the art of calligraphy is so elusive, impossible to catalog or classify. Calligraphy was created long before it appeared on paper, at the very heart of the Universe. If we consider the evolution of painting, the West moved from realism to abstraction in the 20th century. What Picasso once said is intriguing:

If I had been born Chinese, I would have been a calligrapher, not a painter. – Picasso

The mythical beauty of calligraphy fascinated him and encouraged him to pursue a highly abstract style in his masterpieces. Think for a moment. If Picasso was a pioneer of the abstract style in painting or sculpture, in Asia this style remained a standard for millennia. Even today, the Chinese think that painting and calligraphy are sister arts, and the border between them is fluid. Not only do they complement each other, but they are even governed by the same rules: abstract concept, no retouching, use of ink, brush and paper, etc.

In China, it is believed that if someone seeks in art a reflection of the real world, he has the insight of a child. The raw charm of simplicity and a profoundly natural spirituality are the origins of calligraphy. It should never be routine or predictable . Inspirational calligraphy should touch the viewer deep within, even if it is the most abstract work. It must have a musical rhythm, a fascinating and imaginative story, a spectacular aura and an incomparable atmosphere. Everything else is not calligraphy, but a waste of quality ink and paper.

The Tao of Chinese Calligraphy Therapy

Painting

[caption id="attachment_343388" align="alignnone" width="1120"] Chinese art painting[/caption]

Chinese art painting[/caption]

Chinese painting, whose history is already more than twenty centuries old, is considered the true expression of Chinese art. However, she is often poorly known in the West, because her technique and her inspiration are foreign to the conception of painting. The great religions and philosophies that have marked Chinese civilization, Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism, are its main sources of inspiration. Unlike Western painting, it does not seek to render the reality of forms or to give the illusion of space through perspective.

Like calligraphy, which is the art of tracing the characters of Chinese writing, painting is an art of the line, which plays on the modulations of the ink by creating a very rich range of tones. The painter and the calligrapher use the same tools. They both start by diluting their ink stick on their ink stone, using a few drops of water. Then, with a brush, a simple bamboo stick in which animal hair is fixed, they spread the ink on the paper or on the silk, very absorbent materials which allow no repentance. Sitting facing his work table, arm and wrist raised high, the artist paints with a broad movement of the elbow, and of his whole body, without taking a step back.

The most popular materials among early artists were wood and bamboo, but later the following materials were adopted: plastered walls (from 1200 BC), silk (from 300 BC .) and paper (from 100 BC) The use of canvas did not become widespread until the 8th century AD.

Portraits painting

The two most popular subjects in Chinese painting were portraits and landscapes. Portraiture in Chinese art began in the Warring States period (5th to 3rd century BC) and was traditionally executed with great restraint, usually because the subject was a great scholar, a monk or a court official, and therefore had to, by definition, have good character which had to be portrayed with respect by the artist This is why the faces are often seemingly impassive, with only the slightest hint of emotion or character subtly expressed. Often, it is in his attitude and in his relationship with the other people present in the painting that the character of the character is most clearly expressed.

Landscape and literate painting

Landscape painting has been around as long as artists, but the genre really took off during the Tang Dynasty, when artists took a closer look at humanity’s place in nature. In Tang paintings, small human figures guide the viewer through a scenic landscape of mountains and rivers. The theme par excellence of Chinese painting, the landscape owes its development to Taoist philosophy, which seeks a deep communion between man and nature. Its invention is attributed to the poet Wang Wei, year 8th century, who would have been the first to paint in a free and spontaneous way monochrome landscapes in ink. With him was born the tradition of “literate painting”.

It is a painting practiced as amateurs by erudite men of letters, who express in their paintings the emotions that they cannot translate with words. The large Chinese landscape, ranked first in the hierarchy of genres, really asserted itself under the Song dynasty, and from the Yuan it became one of the privileged means of expression. It’s no surprise that mountains and water dominated landscape painting, since the Chinese word for landscape itself literally translates to “mountain and water.” The use of colors was limited, either all in different shades of one color (illustrating the roots of calligraphy) or two colors combined, typically blues and greens.

In keeping with the Taoist belief in the benefits of contemplating serene nature, it is rare for anything to disturb the tranquility of landscape paintings, such as farm workers, and no particular place is intended to be depicted. Later periods, on the other hand, would see more intimate and abstract nature scenes, concentrated on very specific subjects, such as bamboo gardens.

Animals painting

Detailed paintings of a single animal, flower, or bird were particularly popular from the Song dynasty (960-1279 AD), but were considered inferior on the artistic plan to the other categories of Chinese painting. Despite this, certain animals became symbols of certain ideas and appeared in painting as they had already appeared in other art forms such as bronze work.

For example, a pair of mandarin ducks indicated a happy marriage, a stag represented money, and fish represented fertility and abundance. Likewise, plants, flowers and trees had their own meanings. The professional painter prefers delicate colors to those of ink, the meticulous and realistic work of the brush to the spontaneity and the calligraphic line. Flowers and plants, birds and insects, figures and portraits with literary landscapes.

Pottery

[caption id="attachment_343403" align="alignnone" width="1120"] Chinese art pottery[/caption]

Chinese art pottery[/caption]

The Chinese were masters of pottery and ceramics. They produced everything from heavy functional earthenware storage jars to delicately decorated bowls in the finest porcelain, from vases to garden stools, from teapots to pillows. They produced the first glazed pieces, the first green celadons, and the first underglaze pieces painted in cobalt blue. The first advances in techniques and kilns made it possible to reach higher firing temperatures and to obtain the first glazed pottery during the Han period Pottery, especially the gray engobe-painted vessels commonly found in Han tombs, very often imitated the form and decoration of bronze vessels, and this would be the aim of many potters of later periods.

Clay was used to make small unglazed models of ordinary houses which were placed in graves to accompany the dead and, presumably, to symbolically satisfy their need for a new home. Many of these models are completed with adjacent pens and figurines of their occupants and animals. Tang potters achieved a higher level of technical skill than their predecessors. New colored glazes developed at this time included blues, greens, yellows and browns, which were produced with cobalt, iron and copper. Colors were also mixed, producing three-color objects for which the Tang period became famous. Sometimes rich gold and silver inlays were also used to decorate Tang ceramics. The Yuan (1271-1368) and Ming (1368-1644) periods produced even more famous ceramics with their distinctive and much copied blue-on-white decoration, which in turn copied earlier Chinese paintings for design ideas.

Sculpture

[caption id="attachment_343405" align="alignnone" width="1120"] Chinese art sculpture[/caption]

Chinese art sculpture[/caption]

Few people are familiar with the history or qualities of Chinese sculpture; while discussing sculptures, most people will likely think of the ancient Roman architectural sculptures or the Greek nude sculptures. Although very different from its western counterparts, Chinese sculpture has really flourished via a lengthy historical period of growth. In addition to the conventional raw materials of bronze and jade, Chinese sculptors have used a variety of novel raw materials, such as sand and coal, to create delicate items like figures, animals, plants, and landscapes.

In the treasure trove of Chinese art, many of the pieces have developed into priceless creative jewels. Large-scale figure carving has not survived well, but some monumental examples can still be seen, such as those carved into the rock face of the Longmen Grottoes at Fengxian Temple near Luoyang. The 17.4 meter tall figures, dating from 675 CE, depict a Buddhist heavenly king and guardian demons. Shi Huangti’s “Terracotta Army” figurines are another famous example of life-size Chinese sculpture.

The art of the Chinese garden

Art, garden, path and wisdom are terms that are not only compatible, but go hand in hand in the Chinese tradition theorized by scholars. Art, far from designating a technique, or going hand in hand with science, originally means “to plant, cultivate”; it focuses on self-development of the Confucian type, and on the ability to “nurture life within oneself” according to Taoist philosophy, in order to live a long life, even to achieve immortality. “Concentrate your will in the way and delight in the arts,” Confucius urges.

The “arts” in question relate to activities serving the formation of the good man. As for pleasure, it is not understood in the Pascalian sense of entertainment, but of the ability to “be one with the sky” (tianren heyi), according to the traditional adage. Wisdom is thus within the reach of all those who, through their activity or their attitude, seek to achieve harmony, even fusion with the world. The path, the journey, the journey, imaginary or physical, correspond to an essential part of the conception of interior development in China: isn’t Dao (Tao) commonly translated as “Way”? It is precisely the fact of walking, of being on the way towards this Dao, elusive, inconceivable, impalpable through reasoning, language or discourse, which designates wisdom.

Finally, the garden occupies a primordial place in the life of the scholar, generally a civil servant, civil or military, who has prepared, then passed the imperial examinations. Some have failed. Nevertheless, what characterizes the scholar is his daily use of the brush to write and his immense bookish knowledge, the learning of which requires years of sustained effort. Between the 11th and 18th centuries, more and more scholars tended to relax from their administrative activities by practicing the “arts” designated as such, namely poetry, writing, music and painting in a privileged place: their garden. In the Chinese garden designed by scholars, as in the painting of scholars, bamboo is the most popular plant. It symbolizes lasting friendship and longevity. It evokes the values to which scholars, during the Yuan dynasty in particular, are most attached, because they identify with bamboo. Not only because of its proximity to the calligraphic line, to the imprint of the brush, but also because it is flexible, bends under stress, without breaking, and resists, bamboo is often found among the “three friends of winter”: bamboo, pine (for its “uprightness” and “firmness”) and plum blossom for its sensuality and permanent renewal.

]]>